The absolutist register of the NT reflects an anxiety as to whether the potential converts will believe in the doctrine. This leads to some of the most litigious statements in the entire Gospel. He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me: and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. (Matthew again, 10:37-38). But why? Why is something like paternal or filial love supposed to be an obstacle to Jesus Christ, or circumvented and controlled as if it were a potential sin? Just to make sure this is clear, we’re talking about love, and it is being discussed as if it had the implications of a sin. Even more importantly, how illuminated or mature can we consider an ideology to be when it speaks of love as if it were a quantifiable object, that is to say, as though you could say ‘I love my dad with 70% of my spirit but I think I love my mom with 90%, so I’ll love Christ with 120% just to be sure.’ I mean, of course our feelings for people change and grow more or less powerful over the time that we are in touch with them, but it’s not like I’ll love my mother less than I’ll love my wife, or my greatest friend less than my brother, I’ll just love them differently. There’s different forms and expressions of love, and they can be more or less powerful depending on the relationship we have with a person, but it’s still love. It’s still the same core sentiment, whether I feel it lightly for a friend I’ve made in the last month or deeply for someone who is my flesh and blood. And the fact that I love someone very much does not imply that my love for another person is reduced – the amount of love for which there is space in the human heart is, quite simply, infinite. It does not detract from itself. The idea that the Word of God could include such pointless bickering as ‘do you love me more or less than this other chap?’ is unbelievable – it sounds more like the kind of thing a sixteen year-old girl would tell her boyfriend over the phone as a way of flirting.

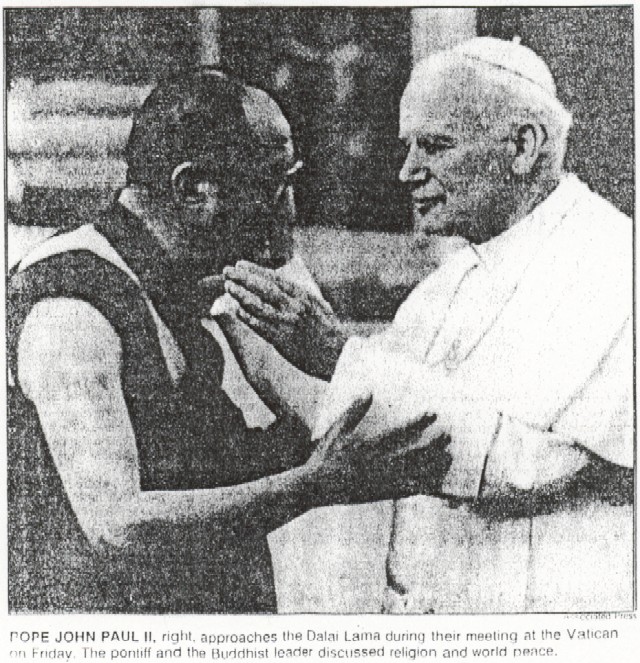

As it endorses the suppression of ideologies only on account of their having a different matrix from its own, Christianity endorses the erasure of difference and therefore richness from the world. It does not acknowledge that as the human spirit grows in infinitely different ways and circumstances, so the solutions that it finds to its problems are infinitely various in form and expression. Some may find illumination in hermitage, others in social life. Some may discover that their vocation is in dancing, others may find it is in writing or cooking, or even in something basically violent like boxing. Some may find that romance works for them when it’s the One True Love, others may discover that flirting and playful seduction with one partner after the other is more their thing. And of course, some may find that their peace in spirit comes not through Christianity but from other religions (if Christianity is imposed on you when you are young, illumination may represent precisely a liberation from Christianity!). I’m not saying that anything goes when it comes to being happy. But I am saying that I don’t buy the notion of one Truth as counterpoised to one Untruth. If Truth were a house, Christianity would be telling us that there is only one path that leads to it, whereas I’m saying that I believe there’s dozens of paths to it, some through the woods, some through the mountains, some through the air or underground, and that it is only walking them, not through doctrine or dogma, which teaches us which one is the right path for us. This is why, to me, the concept that several different Truths can be true at the same time, even if they are contradictory, is so crucial. The paths to Truth and Truth itself are really the same thing. There can be many and one, especially when it comes to the spirit. Heck, even an atheist can find his own way through the woods towards the house of our solitary illumination. The road to the spirit is not restricted to the highways of God.

Since it endorses the erasure of difference from the world, Christianity inevitably leads to conflict between differences – and this is what has led to all the violence in the name of Jesus Christ. People who believe in Jesus Christ think it is correct, and in fact good, to try and homogenize us all into Christianity. Even those who do not enact this belief violently seem to think it. The notion that different individuals require a different good is not one which they recognise – there is only one good, and it is the same for every one. By consequence, anything that does not take part in that good is expendable, if not outright harmful.

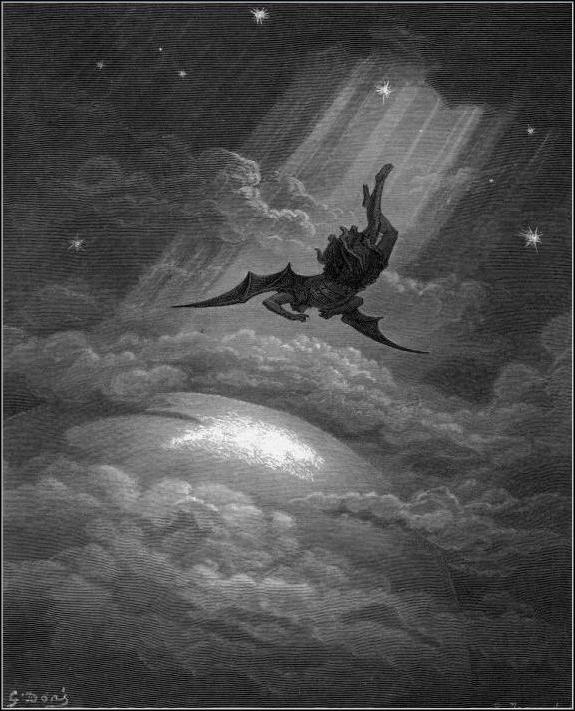

It is this hostility to difference which has led, however indirectly, to Christianity’s considerable history of violence. For this reason, we must recognise that said violence is an implicit outcome of the word of Jesus, not a distortion of the doctrine. Of course, the Gospels do not textually state ‘go out there and kill others,’ but by sending out an absolutist message into a population which they know to be ingenuous, they are responsible for the absolutist interpretations which are derived from it. This is the principle of indirect rhetoric – to draw a paragon for Christianity, the Communist doctrine must be held responsible for the dictatorships that derived from it even though it preached principles which condemned tyranny. This is because Communism released a blueprint for liberalism into its cultures without a safeguard against the power dynamics of the societies which received it. Communists must take responsibility for that, rather than take refuge in negation. Similarly Christianity preached love in terms which would necessarily turn the texts into a weapon to be wielded by authoritarian spirits – simply because the terms are themselves authoritarian. ‘He that is not with me is against me.’ It’s as terribly simple as that.

If I proclaim ‘Black people are bad, but we must respect them and love them,’ it will inevitably and eventually lead to racist violence and discrimination, regardless of the fact that the sentence commands to do the opposite. It is not enough to say the word of peace. You must couch it in a voice of peace as well, in an act of peace as well.

The absolutist register also leads, again indirectly, to one of the greatest paradoxes in current Christian rhetoric. When trying to convert you, Christians will often say that you must take ‘a leap of faith.’ You must open yourself to God and accept Jesus Christ as your Lord and saviour. You must embrace the revelation. This would be fine if it meant opening yourself up to the possibility of Christ being the saviour, but in its enunciation, what it refers to is the certainty that Christ is the Lord. And this is the great fallacy – treating belief as if it were a choice. Genuine belief is not a choice. It is the outcome of experience. You do not switch belief on or off as though it were a lamp. In the ‘leap of faith’ rhetorical routine, belief comes before the experience which allows for it. That’s like imagining a man who is asked to love a girl before he has met her. Yes, clearly ‘leap of faith’ may have different meanings for other people, but if that is the case, then the terms are just terribly chosen. And I’ve had it preached to me often enough that I know this specific fallacy exists and is widespread among Christian communities. Christians essentially pose a request for belief – and more than that, they frame it as an ethical request, as though you had a moral choice on what you believe to be the truth or not.

I mentioned at the beginning of this long critique that it didn’t matter to me whether you believed or not in God, but only whether your belief was a bridge or a wall between yourself and other people. Learning to read the Gospel must be an act of building a bridge. There are many things in the Gospel which we can learn if we are just open to its teachings and if we are willing to learn. But, conversely, there is a dark side to the Gospel, an authoritarian side which we must learn to be wary of – one which teaches us to believe that only through and from Christianity can something come that is good, and that no happiness is real if it is not Christian. This authoritarian side is the part that I cannot endorse and what keeps me from being a Christian, alongside the issues previously discussed. As for my critique, if there is anything I wished to achieve, it was not to dissuade anyone from becoming or being a Christian themselves. I really hope that’s clear. Only I hope to have provided both believers and non-believers alike with a worthy perspective on the dual nature of the Gospels. That the non-believers may learn to recognise the words of love, and that the believers may recognise the seductive and dangerous side of the absolute, which can lead (and has led) to destruction on the earth we share regardless of our faith.

Proud, yeah.

Proud, yeah.

Oooohhh, look at me, I'm flirtatious!

Oooohhh, look at me, I'm flirtatious!