Once upon a time, Hollywood was the land of science-fiction. More so even than in literature, the big screen gave us visions of the future capable of haunting the dreams of generations. The incredible decade ’77-87 gave us, in succession, the Star Wars trilogy, Alien, Blade Runner, The Terminator, Aliens and Robocop. And even the ages before and after that, which graced us with sagas like Star Trek and Planet of the Apes on one side, and Jurassic Park and The Matrix on the other, left a more or less permanent mark on our collective retinas. Yet those times appear completely gone: for almost ten years now (since The Matrix, 1999) there has been no truly groundbreaking science-fiction film, and the genre is left to recycle its own myths in products which range from passable (War of the Worlds) to disappointing (the new Star Wars trilogy, Terminator 3) to downright trash, from the Alien versus Predator bastardisations to the remakes of Rollerball and Planet of the Apes – and all while fantasy blockbusters like Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter dominate the scene. It appears that for the entire first decade of the 21st Century, the big screen has been incapable of visualizing our future.

I want to expend a blog-post to explore the reasons why.

So. The big screen is incapable of visualising our future, we said. This is ironic, because the only interesting thing in science-fiction for a while has been the mutating representations of the screen. To further the irony, it is precisely a recent science-fiction film which best captures the importance of the screen to the imaginary of contemporary culture. Consider the opening (and most memorable) scenes in Spielberg’s Minority Report, a film whose abortive ambition was that of being a new Blade Runner or its equivalent: Tom Cruise, playing a ‘pre-crime’ agent in the future, needs to analyse the visions of a number of oracles to find clues about murders yet to be committed. This process is dubbed ‘scrubbing the image,’ and it involves the character standing before a giant, enveloping screen where images freely pass by. Cruise manipulates these images with no keyboards or other external implements; instead, he wears a set of special gloves and then proceeds to handle the images with his hands. When an image has to be saved, a sheet of glass is connected to the original great screen, then removed with the image on it. It turns out that these sheets of glass which everyone works with are themselves independent, self-sufficient screens, which can be integrated or disconnected at will with other screens.

What is the real meaning of all this? Is there one? Yes – the scene is important because it stages the main theme in our (new) vision of the future, that is to say, the collapse of the notion of border. Look at the scene itself. The room’s main screen slopes gently around the edges, it curves around its user – it is very unclear where it ends (or begins). Simultaneously the manual handling of the images breaks down the distance separating Cruise’s character from the signs he is handling.

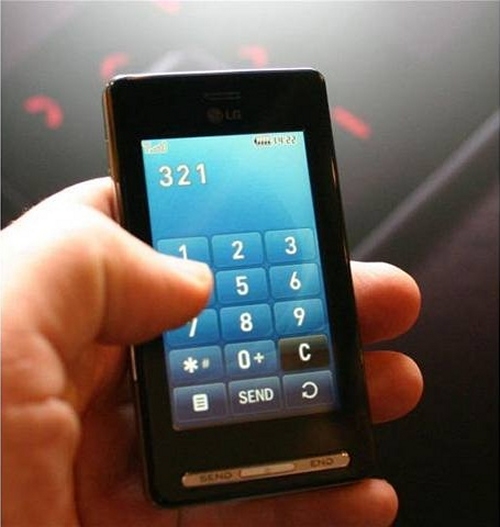

This striking vision, possibly the only truly important one in a film which for the rest came short of almost everything it was trying to be, turns out to be quite pertinent in the light of how we interact with our own screens in real life. A dramatic leap now: consider digital consumer products. The iPhone is fundamentally a large pocket screen, all the functions of which are activated by tactile interaction with its surface (as an aesthetic offspring of the iPod, it is the natural evolution of a system which was already starting to do away with buttons and keyboards). Similarly, the Nintendo DS (‘Double Screen’) portable game system is based around interacting with its videogame worlds by means of a touch-screen, for instance by petting a virtual puppy or drawing shapes directly on screen. Nintendo’s equivalent product for home-use, the Wii, does away with the medium of the joystick and employs a motion-sensing controller which translates hand movements directly onto the screen, reproducing the swing of a bowler or tennis player.

Yadda yadda yadda. So what am I getting at? Well, I’m saying that at the heart of all these products we see a common principle in motion: our ways of interacting with the space behind the screen are being deprived of all the material items and equipment of mediation which separate us from it. This is what it means to see the future now. To collapse our distance from it. Our own external space and the unreal space within the screen are made to collide. Even to correspond: when the border is broken, and mediation ceases, that is when we have a truly pertinent sense of ‘the future,’ one strong enough to get people off their sofas (for a moment) and buying products from the shelves. (I do wish to stress that these are not niche products for an elite consumer base, but true global phenomenons; Nintendo’s systems currently enjoy an overwhelming dominance in their respective markets, outselling the combined efforts of all their competitors put together, and the touch-screen is becoming a standard feature for the latest mobile phone models designed by Sony Ericsson, Nokia, Samsung, and Motorola).

So we’ve got a couple of sketches relating to borders (material or virtual) which smell of the future, but we still don’t understand why. Let’s try taking the question from another perspective – since we are talking about representation here, how do we represent borders? What is the sign of a border, or how do we conceptualise a border?

Let’s invite another source in here through Marshall McLuhan. Who is this McLuhan? Briefly put, he is a guy who has become famous by studying a very simple concept: the medium (actually he became famous by writing a snappy sentence, ‘the medium is the message,’ which caught fire and set ablaze the entire intellectual world and the meaning of which he didn’t really understand, but let’s leave that aside). So before I go waaaayyy too far out on a limb, how does this McLuhan relate to our studies? Well, the guy stated that ‘all media are extensions of some human faculty – psychic or physical. The wheel is an extension of the foot. The book is an extension of the eye… clothing, an extension of the skin… electric circuitry, an extension of the central nervous system.’ Try extending this reasoning to our scenario: the keyboard is, of course, an extension of the hands. Yet the implications of this line of thought are much more far-reaching. For it suggests that the concept of the death of borders which we experience when handling our screens is translated in the imaginary (and in representation) as the death of the medium – and my claim is precisely that it is the death of the medium which has caused the (temporary) death of science-fiction.

The future used to be seen as an amplification of the medium. Classic visions of the future included flying cars, spaceships, robot domestics, fantastic weapons and expansions of ordinary objects (for instance, bathroom utilities). In other words, the future seen as an explosion of the medium of transport, or of warfare, or the instruments for labour or everyday life. As French critic Jean Baudrillard once defined it, the imaginary of science-fiction is ‘an unbounded projection of the real world of production, but… not qualitatively different from it. Mechanical or energetic extensions, speed, and power increase to the nth power, but the schemas and the scenarios are those of mechanics, metallurgy, etc.’.

But Baudrillard’s points, and sci-fi’s cinematographic potential as well, only go that far. In our contemporary imaginary, an item of the future is not one which explodes but one which implodes the medium; this is the principle upon which digital consumer products base their appeal (the same principle which inspired Minority Report's vision): the iPhone and the Wii are sold as advanced, cutting-edge technology because they multiply their functions while nullifying the elements of mediation by which we interact with them. This is the great paradigm shift in terms of how we have come to conceive the future: through the principle of the annihilation of the medium, not of its amplification (or, not anymore).

This is why science-fiction in cinema has given way to fantasy over this decade which is almost past. Sci-Fi’s visions of the future have simply become obsolete.

Perhaps the only recent science-fiction film to have understood this – the only film which truly stands up to the heritage of the great science-fiction films of the past, at least until we see what James Cameron’s Avatar is like – is Pixar’s Wall-E, whose polished satirical bent also touches on all of the above concepts. For, the relationship between the two protagonist robots is (among other things) the juxtaposition of two visions of the future: the mechanical, materially scarred Wall-E, composed of different extensions which he physically replaces (for instance, his ‘legs’), against the unmediated, Mac-looking, flying Eve, whose head, arms and fingers all appear to ‘float’ around the main body without the medium of neck or joints and which can effortlessly be changed into other functions (weapons, scanners) with barely a sign of transition. Eve’s future is the future to which, in Wall-E, humanity belongs: one invaded by screens with simultaneous functions, where all mediums (particularly physical mediums: legs for walking, eyesight, physical contact, not to mention labour and production) have been erased, and all is pulled together and homogenized into the polyfunctional, floating armchairs.

Would people like those depicted in Wall-E understand science-fiction? Could we imagine any representation being displayed in their little screens – anything, that is, except for fantasy?

Coming up part II – an account of the rise of fantasy.

2 comments:

a sensationally good post.

You might be interested in the upcoming movie http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/18/arts/18arts-AUSTENMEETSA_BRF.html?ref=arts

If there is anything that depicts the tragedy of modern Science-fiction it must be the above.

lol, Pride and Predator. I'm so sold.

Thanks for the compliment!

Post a Comment